Massively Parallel Microfluidic Cell-pairing Platform for the Statistical Study of Immunological Cell-cell Interactions

- Category: MEMS & BioMEMS

- Tags: Joel Voldman, Melanie Hoehl

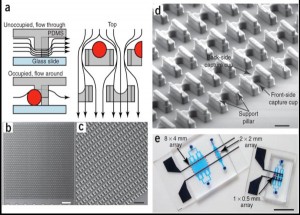

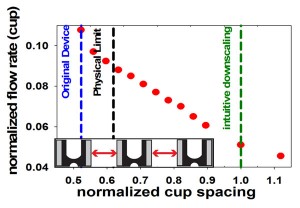

Many immune responses are mediated by cell-cell interactions. In particular, cytotoxic T cells form conjugates with pathogenic and cancer cells in order to fight disease. Moreover, T cell maturation and activation is governed by direct cell interactions with antigen-presenting cells (APCs). Errors in these processes can lead to the progression of severe diseases, such as multiple sclerosis (MS) and type 1 diabetes. The study of these intricate cell-cell interactions at the molecular scale is therefore crucial for understanding the dynamics and specificity of the immune response. One important feature of these interactions is the variability of response across populations. Cell-to-cell variability in presumably homogeneous populations exposed to the same environmental conditions is ubiquitous, yet has long been neglected in immunology due to the limitations of conventional assay methods [1] [2] . Traditional methods to study cell-cell interactions, such as bulk measurements [3] or immobilization of cell pairs on a dish [4] [5] , suffer from both the inability to control cell-pairing at the single cell level and the inability to study dynamic cell-cell interaction processes with high spatial and temporal resolution. We have overcome these limitations by developing a platform that can control cell pairing across thousands of individual immune cell pairs simultaneously while allowing visualization of the resulting responses. This approach enables us to quantify and understand variations in cell-cell interactions within large cell populations at the resolution of individual cell pairs. Previously, we developed a microfluidic device with the capability to create thousands of such single cell pairs for the study of stem cell reprogramming (Figure 1, [6] ). To adapt the approach to work with smaller primary immune cells, we performed hydrodynamic modeling to guide redesign of the trap geometry (Figure 2). The modeling was used to determine how to adjust the trap geometry to maximize flow through the center of the cups, which is crucial to the loading process. We determined that altering the cup-to-cup spacing transverse to the flow had the greatest impact on flow through the cups. We fabricated redesigned traps and are in the process of testing their pairing efficiency with primary immune cells.

- Figure 1: [6] (a) Schematic of the microfluidic device operation and structure. The flow passes under the cell trap, directing the cells into the capture cup. The support pillars maintain the proper vertical gap. (b) Scanning electron micrograph image of the 2 mm x 2 mm device, which contains 1,166 cell traps. (c) Magnified image of the device, showing the densely packed structures. (d) Detail of the trap structure, including the larger front-side and smaller back-side capture cups (14 µm tall, 18µ m wide, 25–40 µm deep, and 10 µm wide by 5 µm deep, respectively), along with support pillars (7.5µ m wide x 35–50 µm long x 6–8 µm tall). (e) Different arrays that can pair and capture thousands of cells in parallel.

- Figure 2: To redesign the cell-pairing device for immune cells, we have established a finite element fluids model. The plot shows the predicted effect of reducing cup spacing (normalized by the downscaled immune cell device) on the relative flow rate through the capture cups. The blue line represents the original cell fusion device. The green line represents simple downscaling of the original device, yielding low flow and, presumably, pairing efficiency. The physical limit (black line) indicates the smallest cup spacing possible that still permits cells to pass between two cups. The model shows that reduc¬ing the horizontal cup spacing can increase flow through the cups and, ultimately, pairing efficiencies for immune cells.

- S. L. Spencer, et al., “Non-genetic origins of cell-to-cell variability in TRAIL-induced apoptosis,” Nature, vol. 459, no. 7245, p. 428, 2009. [↩]

- A. Colman-Lerner, et al., “Regulated cell-to-cell variation in a cell-fate decision system,” Nature, vol. 437, no. 7059, p. 699, 2005. [↩]

- S. Burgdorf, et al., “Distinct pathways of antigen uptake and intracellular routing in CD4 and CD8 T cell activation,” Science, vol. 316, no. 5824, p. 612, 2007. [↩]

- M. S. Fassett, et al., “Signaling at the inhibitory natural killer cell immune synapse regulates lipid raft polarization but not class I MHC clustering,” Proc. National Academy of Sciences, vol. 98, no. 25, p. 14547, 2001. [↩]

- X. Chen, et al., “Many NK cell receptors activate ERK2 and JNK1 to trigger microtubule organizing center and granule polarization and cytotoxicity, “Proc. National Academy of Sciences, vol. 104, no. 15, p. 6329, 2007. [↩]

- A. M. Skelley, et al., “Microfluidic control of cell pairing and fusion,” Nature Methods, vol. 6, no. 2, p. 147, 2009. [↩] [↩]